Within Human Movement, various patterns of compensation and the associated Movement Dysfunction limit an individual’s capability in performance and also dramatically increases the risk of, if not guarantees, a future injury. Conversely, trainers, coaches, and athletes that can identify common patterns of compensation in Human Movement have an opportunity to correct the associative Movement Dysfunctions, restore Biomechanical Integrity, improve Movement Quality, and limit the risk of injury as well as contribute positively to both training and performance.

Fall from Grace

Patterns of Compensation develop in Human Movement for many reasons. From injuries to Daily Life Activities, the Human Body is constantly being shaped and re-modeled through ‘mechanotransduction,’ which is the process in which biomechanical forces in combination with biochemical reactions and energy flows literally ‘deform’ (or change the form of) each and every cell. In addition, mechanotransduction manipulates and modifies corresponding strands of DNA. In other words, Human Movement continuously shapes and re-shapes the Human Body.

What’s most alarming about this relationship between movement and the body is that movement can re-shape the body for the worst, and will at times lessen the body’s capability to function as it could or as it is designed to function. Thus, the scope of Human Movement can have a ‘negative’ influence on the evolution of the Human Body.

Modern Living

As many professionals have already laid claim to in books and research papers, the collective summation of Daily Life Activities (such as texting or sitting) in the Modern World (referring to ‘develop societies’ that utilize a high amount of technology and automation systems for survival) is undermining, if not eroding an individual’s capacity to maintain Biomechanical Integrity and correct joint and tissue function when moving. In short, modern living is making individuals move poorly.

Compensation

A pattern of compensation is the body’s attempt to make up for the lack of movement in one area by adding a new movement. More specifically, a compensation pattern is a neuromuscular strategy of including a ‘new’ firing sequence (Motor Units and Muscles) and/or utilizing structural reliance (bones, ligaments, tendons, fascia and joint structures) to supplement or avoid another firing sequence and/or structural reliance.

Essentially, a compensation pattern is an alternate neuromuscular strategy that the body employs when the naturally prescribed neuromuscular strategy is no longer a viable option to use in the creation of a given movement.

Walking on a limb after an ankle sprain is an example of a compensation pattern. The body simply replaces its normal gait (walking) mechanics with an alternate version or strategy that limits the amount of weight placed on the injured ankle.

Subtle Changes

Many compensation patterns are subtle or hardly noticeable and grow over time to a larger scaled compensation. This ‘domino effect’ is detrimental to an individual’s Biomechanical Integrity and Movement Quality.

A perfect example of the compensation ‘domino effect’ is witnessed in an individual who continually walks or stands on hard, flat surfaces, such as a concrete floor in an average workshop or a steel floor in high-rise building. In each of those environments, the hard, flat floor offers no ‘give’ (malleability or flexibility) as grass, dirt, sand or other natural surfaces do.

Consequentially, the Posterior Tibialis (Calf Muscle) becomes overworked in an effort to maintain a support arch in the foot for the individual who is constantly standing and walking on hard, flat surfaces. This muscle weakens over time due to the repetitive high volume of stress, i.e. attempting to support all the bodyweight over the arch of the foot while standing or walking.

Next, the foot habitually pronates in an excessive manner (allows the arch of the foot to collapse towards the floor), a result of the sequential Movement Dysfunction associated with the weaken Posterior Tibialis muscle. The excessive pronation of the foot adds additional consequences over time.

Dominos Falling

The act of habitually walking on hard, flat surfaces overworks the Posterior Tibialis and allows the arch of the foot to become compromised, eventually collapsing towards the floor. The next domino to fall is the adduction or inward movement of the Tibia (Shin bone) that causes the Peroneals (Lateral Calf Muscles) and Biceps Femoris (Lateral Hamstring Muscles) to eccentrically (negatively) contract as a compensation strategy for neutral alignment and stability of the knee joint. In short, one form or strategy of compensation in Human Movement eventually leads to another and another – no matter how subtle the first form of compensation is at the start.

Patterns Form

In the game dominos, when one tile falls, another is quick to follow, just like compensations and Movement Dysfunctions. When one muscle forms a compensation, another compensation will follow, it’s only a matter of where and when. For example, when the foot continuously pronates (allows for a collapsed arch), then there is a high probability that the Peroneals and Biceps Femoris will become overactive or tight because one Movement Dysfunction leads the way for another Movement Dysfunction. No movement and no Movement Dysfunction ever occurs in the body in isolation. The Human Body is a symbiotic system of physiological structures and Human Movement is an interdependent system of movements and Movement Dysfunctions. Thus, every structure in the body, i.e. joints, muscles, tendons, ligaments, etc., is connected to all other structures within the body.

All of Human Movement, as well as Movement Dysfunctions and Compensation Strategies, exist in ‘patterns’ within the body.

Important to Recognize

Having the ability to recognize patterns of compensation and Movement Dysfunction provides the individual with the opportunity to correct and neutralize the risks and damage associated with patterns, as well as allows the individual to develop more efficiency and integrity in regard to biomechanical functions and Movement Quality.

Unfortunately, if uncorrected or undetected, the patterns of compensation and associated Movement Dysfunctions can and will disrupt Human Movement, increasing the risk of injury and damage to the body, even if the individual is unaware of these risks.

Learning to recognize some of the common patterns of compensation is a reliable tool an individual should use in the effort to minimize risk of injury and damage associated with Movement Dysfunctions.

Common Patterns of Compensation

Many patterns of compensation are ‘common,’ or found in the movement of many individuals across the world, due to the high rate of exposure to the causes of these compensation patterns.

As mentioned before, walking on hard, flat surfaces creates a collapsed arch in the foot and initiates a coordinating pattern of compensation in the body. Most of the modern developed world is equipped with hard, flat surfaces, on which millions, perhaps billions, of people walk and stand every single day. Therefore, the probability that a large number of people experience the same pattern of compensation in their movements is highly likely if not almost definite.

An effective goal for an individual, especially for trainers, coaches and athletes, is to identify common patterns of compensation in Human Movement to address and correct the associated Movement Dysfunctions, limit the risk of injury, and improve Movement Quality.

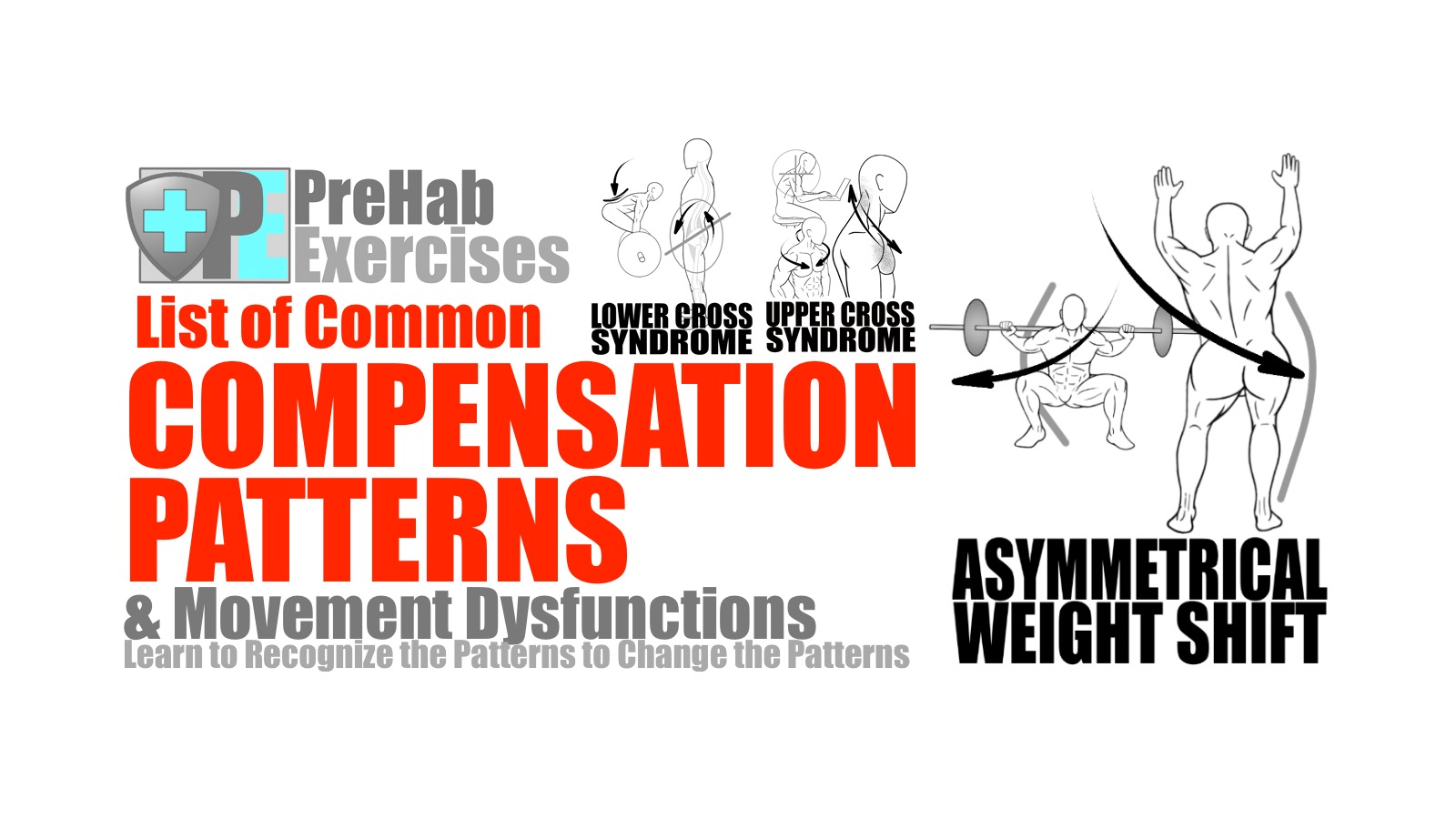

List of Common Patterns of Compensation and Movement Dysfunctions:

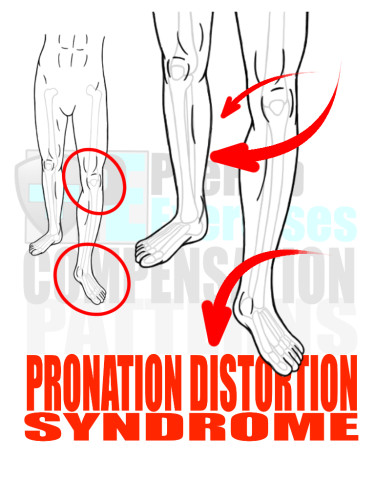

Pronation Distortion Syndrome

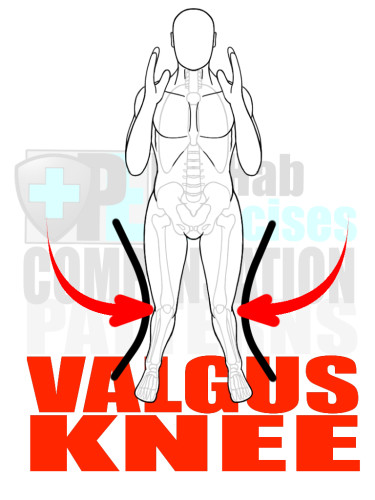

Valgus Knee

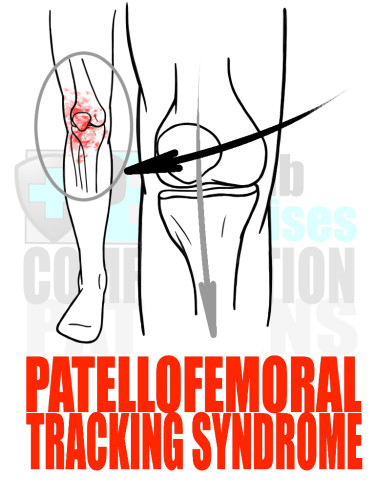

Patellofemoral Tracking Syndrome

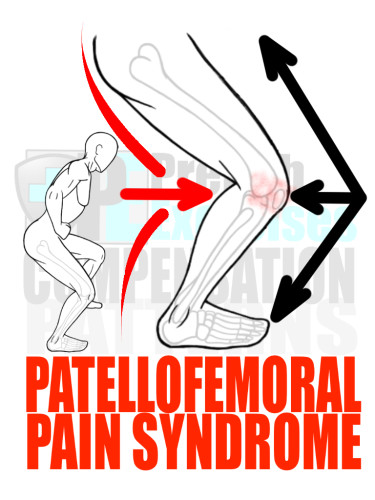

Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome

Quad Dominance

IT Band Syndrome

Asymmetrical Weight Shift

Glute Amnesia Syndrome

Buttwink

Posterior Pelvic Tilt

Anterior Pelvic Tilt

Lower Cross Syndrome

Sway Back – Excessive Lordosis

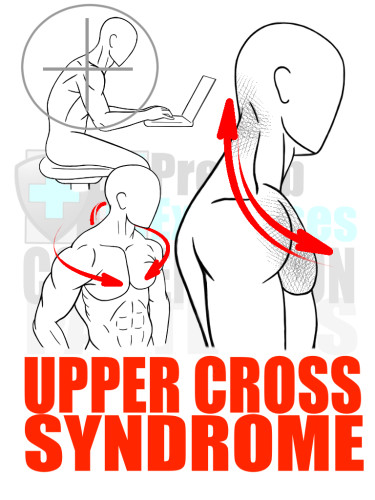

Upper Cross Syndrome

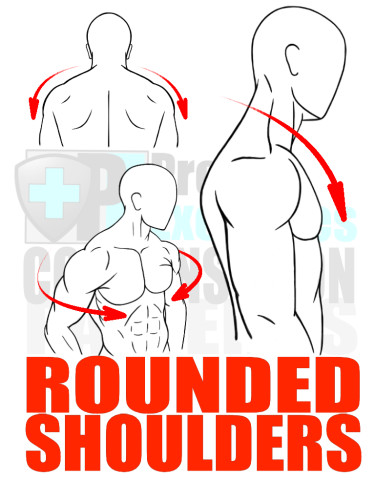

Rounded Shoulders

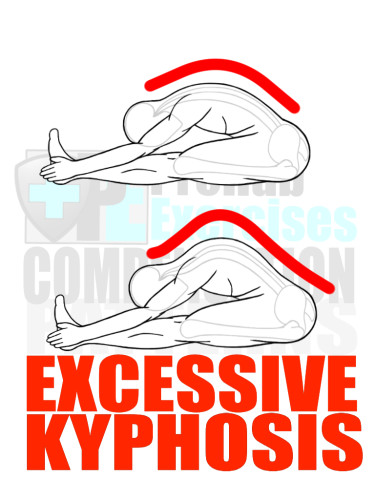

Excessive Kyphosis

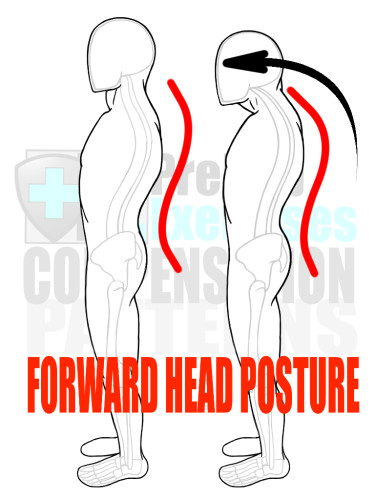

Forward Head Posture

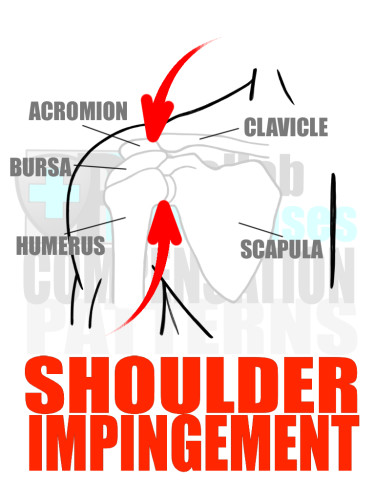

Shoulder Impingement

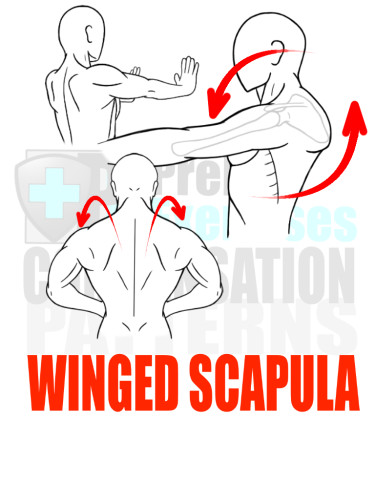

Winged Scapula

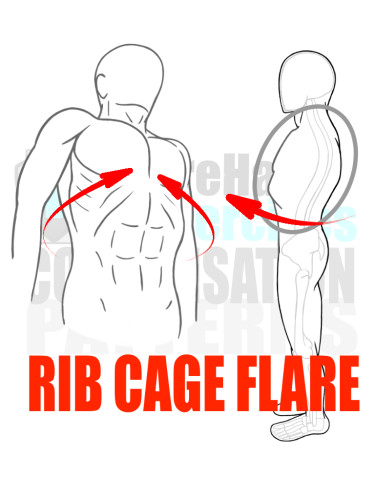

Flared Rib Cage

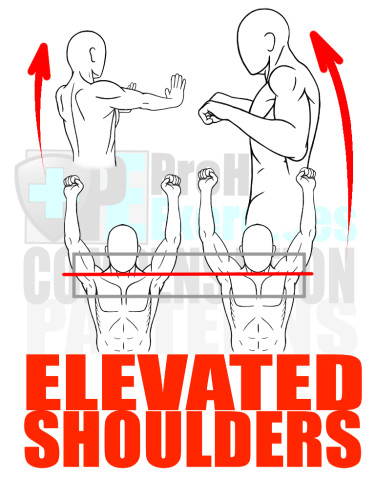

Elevated Shoulders

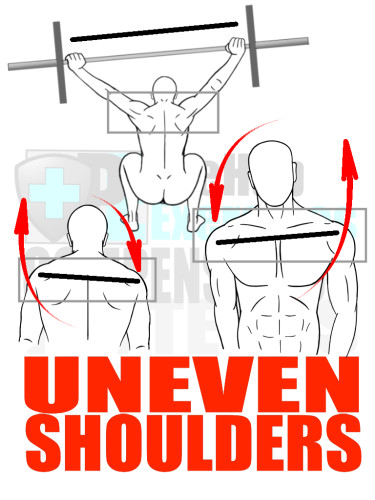

Uneven Shoulders

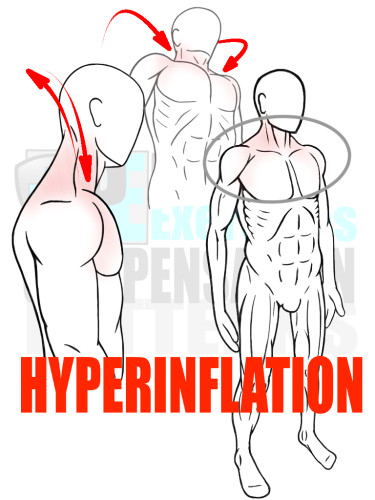

Hyperinflation

What follows is a brief summation of each of these Common Patterns of Compensation that may help an individual identify and address the above Movement Dysfunctions.

Pronation Distortion Syndrome

When assessing an individual’s Biomechanical Integrity and Movement Quality, it is best to start at the bottom of the body as the feet serve as the platform upon which the rest of the body operates. Therefore, it is recommended to start with analyzing for the Pronation Distortion Syndrome.

When the foot excessively pronates and the arch of the foot collapses inward toward the floor, the tibia (shin bone) also collapses inwardly causing a Valgus Knee movement, placing an inappropriate amount of stress on the knee, especially the ACL.

Furthermore, the femur (thigh bone) adducts or collapses toward the midline of the body, which creates tightness in the Vastus Lateralis (Lateral Quadriceps muscle), the Biceps Femoris (Lateral Hamstring muscle), and the Peroneals (Lateral Calf Muscles) as all three muscles eccentrically contract to help stabilize the knee joint. This pattern of compensation leads to the development of a Valgus Knee movement in squatting, lunging, jumping, running, and even standing.

Lastly, Pronation Distortion Syndrome can even cause Low Back Pain as the Hip Flexor complex becomes overactive in the body’s attempt to control the movement of the Femur (thigh bone) and stabilize both knee and pelvis. Eventually, overactive Hip Flexors anteriorly compress the Lumbar Spine and create either an Anterior Tilt of the pelvis and/or excessive Lordotic Extension of the spine, referred to as Sway Back.

RX: Start practicing a combination of soft tissue therapy and effective stretching techniques on the following overactive or tight muscles: Peroneals (Lateral Calf), Biceps Femoris (Lateral Hamstring), Vastus Lateralis (Lateral Quadriceps), Adductor Complex (Groin Muscles), Tensor Fasciae Latae (TFL – Hip Flexor) and Psoas (Hip Flexors). Also, practice soft tissue therapy on the Posterior Tibialis (Interior Calf Muscle) and the Gastrocnemius (Calf Muscle) to activate and induce the responsiveness of soft tissue in these muscles to properly align and supinate the foot, i.e. strengthen the arch of the foot.

Next, practice Activation exercises to strengthen and facilitate proper firing sequences of the following underactive muscles: Gluteus Medias (Lateral Hip Muscle), Posterior Tibialis (Interior Calf Muscle), Gastrocnemius (Calf Muscle) and the Intrinsic Foot Muscles.

Finally, practice a variety of exercises integrating these underactive muscles with larger Movement Patterns, including squatting, lunging, and running. Also, challenge stability, coordination, and balance with single-leg and/or Change of Direction (C.O.D.) exercises.

Valgus Knee

A Valgus Knee movement is an involuntary inward movement of the knee joint, caused by a lack of Stability in the Ankle and/or Hip. It is also influenced by the following overactive muscle groups: Vastus Lateralis (Lateral Quadriceps muscle), Biceps Femoris (Lateral Hamstring muscle), and Peroneals (Lateral Calf Muscles).

A Valgus Knee movement will disrupt the proper patellofemoral tracking (tracking in the knee joint) and place an inappropriate amount of stress on the ACL.

RX: Practice a combination of soft tissue therapy and effective stretching techniques on the following overactive and/or tight muscles: Peroneals (Lateral Calf Muscles), Biceps Femoris (Lateral Hamstring), Vastus Lateralis (Lateral Quadriceps), the Adductor Complex (Groin Muscles), and Psoas (Hip Flexors).

Next, practice Activation exercises to strengthen and facilitate proper firing sequences of the following underactive muscles: Gluteus Medias (Lateral Hip Muscle), Posterior Tibialis (Interior Calf Muscle), Gastrocnemius (Calf Muscle) and the Intrinsic Foot Muscles.

Finally, practice a variety of exercises integrating these underactive muscles with larger Movement Patterns, including squatting, lunging/step-ups, and running. Also, challenge stability, coordination, and balance with single-leg and/or Change of Direction (C.O.D.) exercises.

Patellofemoral Tracking Syndrome

The structure of the knee is designed with two condyles (shallow grooves) that cradle the intercondylar fossa (two notches on the end of the femur) and a sliding flat bone known as the patella (kneecap) that forms a bracket and guides the rotational motion of the knee.

When the tracking or movement of the knee becomes distorted due to Valgus Knee movements, Quad Dominance, and other compensation patterns or movement dysfunctions, the movement dysfunction is referred to as Patellofemoral Tracking Syndrome.

There are two main types of Patellofemoral Tracking Syndrome. The first includes a lateral shift in the positioning of the Patella (kneecap) as the knee flexes or extends. This type is usually associated with a Valgus Knee Movement. The second type of Patellofemoral Tracking Syndrome occurs when there is too much tension or shortening in the Quadriceps. This continuously pulls the patella (kneecap) into the distal (bottom) end of the Femur (thigh bone) while the knee flexes or extends. This type of Patellofemoral Tracking Syndrome is heavily associated with Quad Dominance and leads to Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome or Knee Pain.

RX: Practice a combination of soft tissue therapy and effective stretching techniques on the following overactive and/or tight muscles: Quadriceps (Anterior Leg Muscles), Peroneals (Lateral Calf Muscles), Biceps Femoris (Lateral Hamstring), and the Adductor Complex (Groin Muscles).

Next, practice Activation exercises to strengthen and facilitate proper firing sequences of the following underactive muscles: Vastus Medial Oblique (VMO – Medial/Inside Quadriceps), Internal/External Hip Rotators, Gluteus Medias (Lateral Hip Muscle), Posterior Tibialis (Interior Calf Muscle), Gastrocnemius (Calf Muscle), and the Intrinsic Foot Muscles.

Finally, practice a variety of exercises integrating these underactive muscles with larger Movement Patterns, including squatting, lunging/step-ups, and running. Also, challenge stability, coordination, and balance with single-leg and/or Change of Direction (C.O.D.) exercises.

Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome

Pain that occurs at the front of the knee and regularly just behind the kneecap is generally categorized as Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome. This knee pain is frequently a result of a type of Patellofemoral Tracking Syndrome where the patella (kneecap) is continuously pressed or pulled into the bottom of the femur, resulting in an increased amount of friction and wear-and-tear on the structures of the knee.

Patellofemoral Pain Syndrome is greatly influenced by repetitive movements, i.e. running, combined with lifestyle factors, i.e. sitting, that create a pattern of compensation called Quad Dominance.

RX: Practice a combination of soft tissue therapy and effective stretching techniques on the following overactive and/or tight muscles: Quadriceps (Anterior Leg Muscles), Peroneals (Lateral Calf Muscles), Biceps Femoris (Lateral Hamstring), and the Adductor Complex (Groin Muscles).

Next, practice Activation exercises to strengthen and facilitate proper firing sequences of the following underactive muscles: Vastus Medial Oblique (VMO – Medial/Inside Quadriceps), Internal/External Hip Rotators, Gluteus Medias (Lateral Hip Muscle), Posterior Tibialis (Interior Calf Muscle), Gastrocnemius (Calf Muscle), and the Intrinsic Foot Muscles.

Finally, practice a variety of exercises integrating these underactive muscles with larger Movement Patterns, including squatting, lunging/step-ups, and running. Also, challenge stability, coordination and balance with single-leg and/or Change of Direction (C.O.D.) exercises.

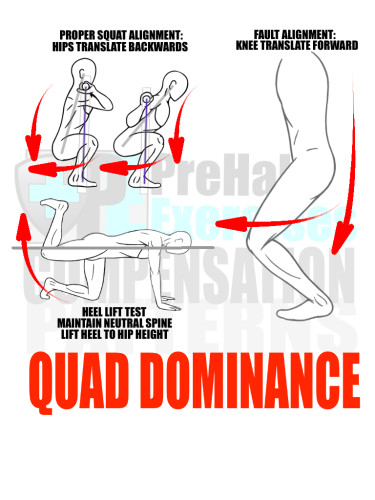

Quad Dominance

This pattern of compensation is a type of ‘Synergist Dominance’ pattern in movement, wherein one of the synergist or assisting muscles begins to overly compensate for the prime mover or agonist muscle within a specific movement pattern.

Quad Dominance refers to the pattern in which the Quadriceps (thigh muscles) are overactive and compensate/take over for the Gluteus and Hamstring muscles in movements that include squatting, lunging, jumping, running and standing.

Quad Dominance is tied to another Movement Dysfunction called Glute Amnesia Syndrome; the Gluteus muscles are inhibited or ‘turned off’ due to inactivity, a lack of appropriate neural drive and lifestyle factors, which includes sitting.

RX: Practice a combination of soft tissue therapy and effective stretching techniques on the following overactive and/or tight muscles: Quadriceps (Anterior Leg Muscles), Psoas (Deep Hip Flexor), Tensor Fasciae Latae (TFL – Superficial Hip Flexor), and the Adductor Complex (Groin Muscles).

Next, practice Activation exercises to strengthen and facilitate proper firing sequences of the following underactive muscles: Gluteus Complex (Posterior Hip Muscle), Hamstring Complex (Posterior Leg Muscles), and Transverse Abdominis/Obliques (Core Muscles).

Finally, practice a variety of exercises integrating these underactive muscles with larger Movement Patterns, including squatting, lunging/step-ups, jumping, running, and even standing. Also challenge stability, coordination, and balance with single-leg and/or Change of Direction (C.O.D.) exercises.

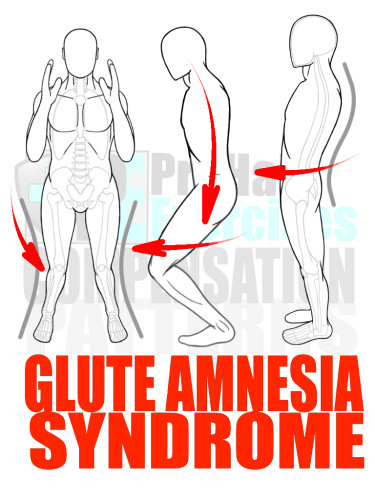

Glute Amnesia Syndrome

As mentioned above, Glute Amnesia Syndrome is a Movement Dysfunction where the Gluteus or Posterior Hip Muscles are not used enough, therefore inhibiting, or “turning off,” the neuromuscular connections.

The neuromuscular connections do not truly turn off; instead, the body remodels its Motor Behavior (neuromuscular coordination) to use an alternate pattern of Motor Control to perform certain tasks. Over time, this pattern of compensation is solidified as a pattern of Motor Behavior or it becomes a ‘Movement Habit’ in which an individual neglects to activate and use his or her Glutes (Hip Muscles) to execute specific movements including squatting, lunging, and running.

RX: Practice a combination of soft tissue therapy and effective stretching techniques on the following overactive and/or tight muscles: Quadriceps (Anterior Leg Muscles), Psoas (Deep Hip Flexor), Tensor Fasciae Latae (TFL – Superficial Hip Flexor), the Adductor Complex (Groin Muscles), Peroneals (Lateral Calf Muscles), and Biceps Femoris (Lateral Hamstring Muscles).

Next, practice Activation exercises to strengthen and facilitate proper firing sequences of the following underactive muscles: Gluteus Complex (Posterior Hip Muscle), Piriformis (Posterior Hip Muscle), Semitendinosus (Medial/Middle Hamstring Muscles), Gastrocnemius (Calf Muscles), the Intrinsic Foot Muscles, and Transverse Abdominis/Obliques (Core Muscles).

Finally, practice a variety of exercises integrating these underactive muscles with larger Movement Patterns, including squatting, lunging/step-ups, jumping, running, and even standing. Also, challenge stability, coordination, and balance with single-leg and/or Change of Direction (C.O.D.) exercises.

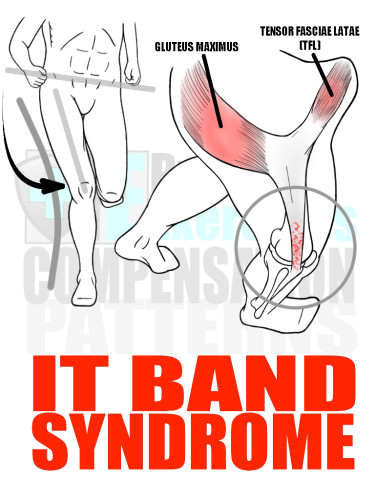

IT Band Syndrome

Another Movement Dysfunction and pattern of compensation tied to Glute Amnesia Syndrome and Pronation Distortion Syndrome is IT Band Syndrome.

IT Band Syndrome is the process in which the Iliotibial Tendon (IT Band) that connects the Tensor Fasciae Latae (TFL) to the Tibia (shine bone) becomes inflamed and sensitive due to an inappropriate amount of stress being placed on the soft tissue structure.

IT Band Syndrome usually occurs in individuals who do not properly activate their Gluteus Complex, specifically the Gluteus Medius, and/or do not properly activate their intrinsic foot muscles and medial Gastrocnemius (Calf Muscles) to provide adequate amount of control and stability in the movements of the knee. Consequentially, the TFL and IT Band attempt to provide stability to the knee from a mechanically disadvantaged position. The end result is prolonged inflammation and sensitivity to the IT Band from the wear-and-tear and stress of the compensation pattern.

RX: Practice a combination of soft tissue therapy and effective stretching techniques on the following overactive and/or tight muscles: Tensor Fasciae Latae (TFL – Superficial Hip Flexor), Gluteus Maximus (Posterior Hip Muscles), Vastus Lateralis (Lateral Quadriceps), Peroneals (Lateral Calf Muscles), and Biceps Femoris (Lateral Hamstring Muscles).

Next, practice Activation exercises to strengthen and facilitate proper firing sequences of the following underactive muscles: Gluteus Medius (Lateral Hip Muscle), Piriformis (Posterior Hip Muscle), Internal/External Hip Rotators, Semitendinosus (Medial/Middle Hamstring Muscles), Gastrocnemius (Calf Muscles), the Intrinsic Foot Muscles, and Transverse Abdominis/Obliques (Core Muscles).

Finally, practice a variety of exercises integrating these underactive muscles with larger Movement Patterns, including squatting, lunging/step-ups, jumping, running and even standing. Also, challenge stability, coordination, and balance with single-leg and/or Change of Direction (C.O.D.) exercises.

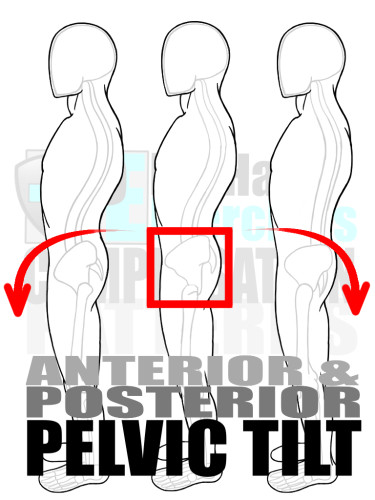

Anterior Pelvic Tilt

After assessing the feet and knees for compensations, the next area assessed is the pelvic region or Hips. The Hips are the foundation and platform on which the Spine and Upper Body operates. All patterns of compensation and dysfunctions in the Pelvic region have an effect on the movement and alignment of the Upper Body.

One common pattern of compensation is an Anterior Tilt of the Pelvis. An Anterior Tilt means the top of the Pelvis rotates to the front of the body, creating an exaggerated extension of the Lumbar Spine and possibly the Thoracic and/or Cervical Spine as well. An Anterior Tilt is commonly caused by a combination of overactive muscles, namely the Hip Flexors and the Latissimus Dorsi.

The trouble with an Anterior Tilt is that it places an uneven amount of strain on the vertebrae and discs of the Lumbar Spine (Lower Back), and can also disrupt the alignment of the Thoracic Spine, Rib Cage, Shoulders, and Head.

An Anterior Tilt can be linked to Pronation Distortion Syndrome, Glute Amnesia Syndrome, IT Band Syndrome, and Quad Dominance. Furthermore, it can create even more patterns of compensation or dysfunction including Forward Head, Upper Cross Syndrome, Hyperinflation, and Low Back Pain.

RX: Practice a combination of soft tissue therapy and effective stretching techniques on the following overactive and/or tight muscles: Psoas (Deep Hip Flexors), Tensor Fasciae Latae (TFL – Superficial Hip Flexor), Latissimus Dorsi (Back Muscles), Thoracolumbar Fascia (Fascia Sheath of the Lower Back), Lower Erector Spinae (Low Back Muscles), Lower Multifidus (Low Back Muscles), Iliocostalis Lumborum (Low Back Muscles), Quadratus Lumborum (Low Back Muscles), Posterior Portion of the External Obliques (Posterior Core Muscles), Quadriceps (Anterior Leg Muscles), the Adductor Complex (Groin Muscles), Peroneals (Lateral Calf Muscles), and Biceps Femoris (Lateral Hamstring Muscles).

Next, practice Activation exercises to strengthen and facilitate proper firing sequences of the following underactive muscles: Gluteus Complex (Posterior Hip Muscle), Piriformis (Posterior Hip Muscle), Internal/External Hip Rotators, Rectus Abdominis (Anterior Core Muscles), Anterior Portion of Internal/External Obliques (Anterior/Lateral Core Muscles), Semitendinosus (Medial/Middle Hamstring Muscles), Gastrocnemius (Calf Muscles), the Intrinsic Foot Muscles, and Transverse Abdominis/Obliques (Core Muscles).

Finally, practice a variety of exercises integrating these underactive muscles with larger Movement Patterns, including squatting, lunging/step-ups, jumping, running, and even standing. Also, challenge stability, coordination, and balance with single-leg and/or Change of Direction (C.O.D.) exercises.

Posterior Pelvic Tilt

Counter to an Anterior Pelvic Tilt is the Posterior Pelvic Tilt, in which the top of the Pelvis is rotated toward the back of the body.

A Posterior Pelvic Tilt places an unbalanced amount of strain on the vertebrae and discs of the Lumbar Spine (Low Back), which can lead to other patterns of compensation, such as Sway Back, while also effecting the movement and alignment of the Upper Body.

RX: Practice a combination of soft tissue therapy and effective stretching techniques on the following overactive and/or tight muscles: Gluteus Complex (Posterior Hip Muscle), Piriformis (Posterior Hip Muscle), Internal/External Hip Rotators, Rectus Abdominis (Anterior Core Muscles), Anterior Portion of Internal/External Obliques (Anterior/Lateral Core Muscles), Semitendinosus (Medial/Middle Hamstring Muscles), and Gastrocnemius (Calf Muscles).

Next, practice Activation exercises to strengthen and facilitate proper firing sequences of the following underactive muscles: Lower Erector Spinae (Low Back Muscles), Lower Multifidus (Low Back Muscles), Iliocostalis Lumborum (Low Back Muscles), Quadratus Lumborum (Low Back Muscles), Posterior Portion of the External Obliques (Posterior Core Muscles), Psoas (Deep Hip Flexors), Tensor Fasciae Latae (TFL – Superficial Hip Flexor), Quadriceps (Anterior Leg Muscles), and the Intrinsic Foot Muscles.

Finally, practice a variety of exercises integrating these underactive muscles with larger Movement Patterns, including squatting, lunging/step-ups, jumping, running, and even standing. Also, challenge stability, coordination, and balance with single-leg and/or Change of Direction (C.O.D.) exercises.

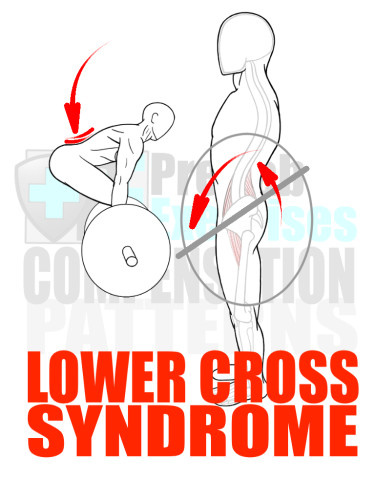

Lower Cross Syndrome

An Anterior Pelvic Tilt plays a central role in Lower Cross Syndrome, a compensation pattern involving strength or muscle imbalances around the Pelvis.

A Strength or Muscle Imbalance occurs in the body when one set of muscles grows disproportionately stronger than a reciprocal set of muscles attached to the same joint complex or bone structure. In the Lower Cross Syndrome, two concurrent Strength or Muscle Imbalances are evident; the Hip Flexors have grown muscles stronger and/or tighter than the Hamstring complex and the Posterior Trunk (Low Back) Extensors have grown much stronger and/or tighter than the Anterior Trunk (Abdominals) Flexors. This strength dominance of the Hip Flexors and Low Back Extensors results in the shifting of the Pelvis into an Anterior Tilt.

The Lower Cross Syndrome further disrupts an individual’s movement as the compensation pattern becomes both a static posture and a habitual dynamic alignment. This habit causes the individual to learn and initiate all movement with the compensation, resulting in a repetitive Movement Dysfunction that places an inappropriate amount of stress on the vertebrae and discs of the Lumbar Spine, ultimately leading to Low Back Pain and/or injury.

Habitual and prolonged periods of sitting increase an individual’s risk of developing Lower Cross Syndrome.

RX: Practice a combination of soft tissue therapy and effective stretching techniques on the following overactive and/or tight muscles: Psoas (Deep Hip Flexors), Tensor Fasciae Latae (TFL – Superficial Hip Flexor), Latissimus Dorsi (Back Muscles), Thoracolumbar Fascia (Fascia Sheath of the Lower Back), Lower Erector Spinae (Low Back Muscles), Lower Multifidus (Low Back Muscles), Iliocostalis Lumborum (Low Back Muscles), Quadratus Lumborum (Low Back Muscles), Posterior Portion of the External Obliques (Posterior Core Muscles), Quadriceps (Anterior Leg Muscles), the Adductor Complex (Groin Muscles), Peroneals (Lateral Calf Muscles) and Biceps Femoris (Lateral Hamstring Muscles).

Next, practice Activation exercises to strengthen and facilitate proper firing sequences of the following underactive muscles: Gluteus Complex (Posterior Hip Muscle), Piriformis (Posterior Hip Muscle), Internal/External Hip Rotators, Rectus Abdominis (Anterior Core Muscles), Anterior Portion of Internal/External Obliques (Anterior/Lateral Core Muscles), Semitendinosus (Medial/Middle Hamstring Muscles), Gastrocnemius (Calf Muscles), the Intrinsic Foot Muscles, and Transverse Abdominis/Obliques (Core Muscles).

Finally, practice a variety of exercises integrating these underactive muscles with larger Movement Patterns, including squatting, lunging/step-ups, jumping, running, and even standing. Also, challenge stability, coordination, and balance with single-leg and/or Change of Direction (C.O.D.) exercises.

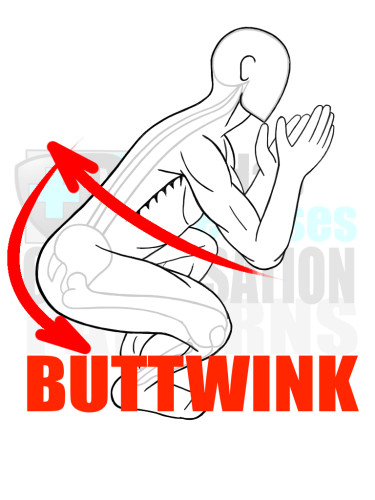

Buttwink

The Buttwink is a compensation pattern involving a dynamic Posterior Pelvis Tilt during Hip Flexion that occurs in a squatting or Hip Hinging movement. More specifically, the Buttwink is a compensation pattern that attempts to increase the Range of Motion of the Hip and/or Ankle by rotating the Pelvis and flexing through the Lumbar Spine.

The danger of this compensation pattern is the inappropriate amount of stress placed on anterior portions of the vertebrae and discs in the Lumbar Spine (Low Back). This can cause episodes of acute micro-trauma, eventually leading to disc herniation and/or Low Back Pain.

The Buttwink robs an individual of biomechanical integrity of the spine in regard to alignment and stability; many times the individual may not be aware this compensation pattern is occurring.

RX: Practice a combination of soft tissue therapy and effective stretching techniques on the following overactive and/or tight muscles: Gluteus Complex (Posterior Hip Muscle), Piriformis (Posterior Hip Muscle), Internal/External Hip Rotators, Rectus Abdominis (Anterior Core Muscles), Anterior Portion of Internal/External Obliques (Anterior/Lateral Core Muscles), Semitendinosus (Medial/Middle Hamstring Muscles), and Gastrocnemius (Calf Muscles).

Next, practice Activation exercises to strengthen and facilitate proper firing sequences of the following underactive muscles: Lower Erector Spinae (Low Back Muscles), Lower Multifidus (Low Back Muscles), Iliocostalis Lumborum (Low Back Muscles), Quadratus Lumborum (Low Back Muscles), Posterior Portion of the External Obliques (Posterior Core Muscles), Psoas (Deep Hip Flexors), Tensor Fasciae Latae (TFL – Superficial Hip Flexor), Quadriceps (Anterior Leg Muscles), and the Intrinsic Foot Muscles.

Finally, practice a variety of exercises integrating these underactive muscles with larger Movement Patterns, including squatting, lunging/step-ups, jumping, running, and even standing. Also, challenge stability, coordination, and balance with single-leg and/or Change of Direction (C.O.D.) exercises.

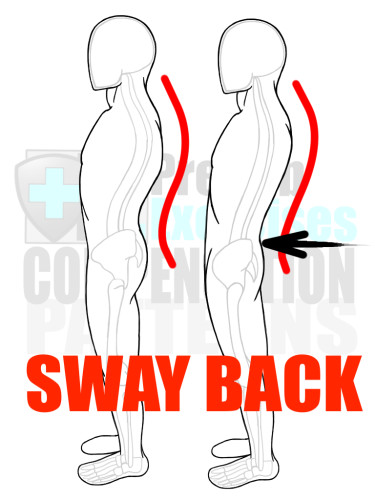

Sway Back

Another compensation pattern effecting the alignment of the Lumbar Spine (Low Back) is Sway Back. In this compensation pattern, the Lumbar Spine (Low Back) has an excessive amount of extension, placing an inappropriate and unbalanced amount of pressure on the vertebrae and discs.

Sway Back occurs due to many different reasons and is characterized by a posture with protruding (forward) Hips and an excessive arch in the Lower Back. Many times, Sway Back is caused by a combination of tightness and/or overactive Hamstrings and Posterior Trunk (Low Back) Extensors. Sometimes, a tight and/or overactive Piriformis muscle contributes to the protruding Hips. Regardless of the cause, Sway Back is dangerous to the biomechanical integrity and health of the Lumbar Spine and may lead to Low Back Pain.

RX: Practice a combination of soft tissue therapy and effective stretching techniques on the following overactive and/or tight muscles: Gluteus Complex (Posterior Hip Muscle), Piriformis (Posterior Hip Muscle), Internal/External Hip Rotators, Psoas (Deep Hip Flexors), Tensor Fasciae Latae (TFL – Superficial Hip Flexor), Semitendinosus (Medial/Middle Hamstring Muscles), Lower Erector Spinae (Low Back Muscles), Lower Multifidus (Low Back Muscles), Iliocostalis Lumborum (Low Back Muscles), and Quadratus Lumborum (Low Back Muscles).

Next, practice Activation exercises to strengthen and facilitate proper firing sequences of the following underactive muscles: Rectus Abdominis (Anterior Core Muslces), Internal/External Obliques (Lateral Core Muscles), Transverse Abdominis (Interior Core Muscles), Quadriceps (Anterior Leg Muscles), and the Intrinsic Foot Muscles.

Finally, practice a variety of exercises integrating these underactive muscles with larger Movement Patterns, including squatting, lunging/step-ups, jumping, running, and even standing. Also, challenge stability, coordination, and balance with single-leg and/or Change of Direction (C.O.D.) exercises.

Low Back Pain

The National Academy of Sports Medicine reports that 80% of adults will experience Low Back Pain at some point in their lives. This is highly likely considering the anatomical design of the Human Skeleton. There is a lack of structural support connecting the upper body to the lower body, and the Lumbar Spine is the only boney structure bridging the two halves of the body together.

All the compensation patterns previously mentioned, as well as the ones still to come, negatively impact the biomechanical integrity of the Lumbar Spine (Low Back), especially in regards to alignment and stability.

To reduce, eliminate, or prevent Low Back Pain, an individual’s alignment and stability of the Lumbar Spine must be addressed and integrated into a training program.

RX: Practice a combination of soft tissue therapy and effective stretching techniques on all of the muscles that connect to both the Spine and the Pelvis, as well as for the muscles that operate within the Foot/Ankle and Shoulder/Neck Complexes. This ultimately means the entire body needs to be treated with soft tissue therapy and effective stretching techniques.

Next, practice Activation exercises to strengthen and facilitate proper firing sequences to as many muscle groups as possible in the entire body, especially the muscle groups that connect to the Spine and Pelvis as well as muscles that run through the Foot and Ankle complex.

Finally, practice a variety of exercises that use the major joint structures (i.e. Foot/Ankle, Hip, Spine and Shoulders) in smooth and controlled movements. Smooth movements must be accomplished before practicing larger Movement Patterns, such as squatting, lunging/step-ups, jumping, and running. Once movement is completed in a controlled and stable fashion, then challenge stability, coordination, and balance with single-leg and/or Change of Direction (C.O.D.) exercises.

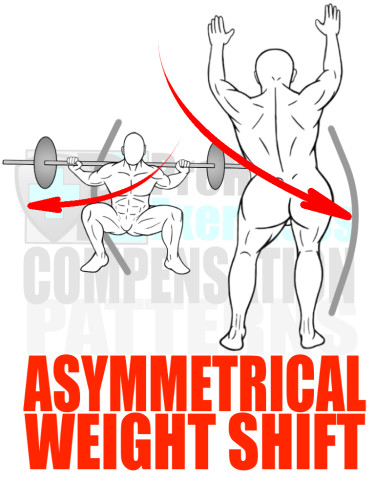

Asymmetrical Weight Shift

Another common pattern of compensation is an Asymmetrical Weight Shift, or the habitual process of shifting one’s weight over to one specific leg while squatting and/or standing, as well as in pushing and pulling movements.

An Asymmetrical Weight Shift is an indication that a Strength Imbalance exists somewhere in body. One limb or one side of the Pelvis and/or Torso is compensating for the weakness and/or dysfunction of the opposite limb or side of the Pelvis and/or Torso.

The causes of an Asymmetrical Weight Shift are as vast as the number of Strength Imbalance combinations possible in the body… very large. However, assessing the movement efficiency and Range of Motion of various joints involved in creating a given Movement Pattern are an effective guide to uncovering and evaluating the specific details of any possible Strength Imbalance.

RX: When an Asymmetrical Weight Shift is observed, assess the Biomechanical Integrity of each joint involved in the given Movement Pattern to uncover the possible Strength or Muscle Imbalance affecting the individual’s movement.

Start with a combination of soft tissue therapy and effective stretching techniques on all muscles that connect to both the Spine and the Pelvis in addition to the muscles that operate within the Foot/Ankle and Shoulder/Neck Complexes. This ultimately means the entire body needs to be treated with soft tissue therapy and effective stretching techniques.

Next, practice Activation exercises to strengthen and facilitate proper firing sequences to as many muscle groups as possible in the entire body, especially the muscle groups that connect to the Spine and Pelvis as well as the muscles that run through the Foot and Ankle complex.

Finally, practice a variety of exercises that use the major joint structures (i.e. Foot/Ankle, Hip, Spine and Shoulders) in smooth and controlled movements. Smooth movements must be accomplished before practicing larger Movement Patterns, such as squatting, lunging/step-ups, jumping, and running. Once movement is completed in a controlled and stable fashion, then challenge stability, coordination, and balance with single-leg and/or Change of Direction (C.O.D.) exercises.

Flared Rib Cage

When the lower ribs protrude forward and stick out, this is a sign that the Core musculature is experiencing a Strength or Muscle Imbalance; the alignment and stability of the Lumbar Spine is being compromised.

A Flared Rib Cage points to overactive and/or tight Posterior Trunk muscles that are attempting to manage and stabilize the Spine without adequate amount of assistance from the Anterior Trunk muscles, including the Internal/External Obliques and Abdominals. This Strength or Muscle Imbalance places a disproportionate amount of strain on the vertebrae and discs of the Lumbar Spine (Low Back) and may lead to Low Back Pain as well as other Movement Dysfunctions and compensation patterns.

RX: Practice a combination of soft tissue therapy and effective stretching techniques on muscles that connect around the top of the Rib Cage, especially the First Rib, which includes the Upper Trapezius (Neck and Shoulder Muscle), Scalenes (Neck Muscles), Pectoral Complex (Chest Muscles), and the Latissimus Dorsi (Back Muscles).

Next, practice Activation exercises to strengthen and facilitate proper firing sequences of the following muscles: Diaphragm (Deep Core Muscle), Internal/External Obilques (Lateral Core Muscles), Multifidus (Posterior Core Muscles), and the Transverse Abdominis (Core Muscle).

Finally, practice a variety of breathing exercises that emphasize exhalation. Also practice exercises that integrate the firing sequences practiced in Core Activation exercises with larger Movement Patterns, such as squatting, lunging, running, etc. Once integration is achieved and Rib Flare is eliminated, continue to integrate the Core Firing sequence into exercises that challenge stability, coordination, and balance, i.e. single-leg and/or Change of Direction (C.O.D.) exercises.

Excessive Kyphosis

A hunchback is an exaggerated example of excessive Kyphosis, which is the forward flexion or rounding of the Thoracic Spine (vertebrae that run through the Rib Cage). The Thoracic Spine has a natural Kyphotic or forward curve to its alignment. However, this forward curvature can increase resulting in a Movement Dysfunction that affects the Shoulders, Head, Lumbar Spine (Low Back) and Hips.

An Excessive Kyphotic Spine can be observed in a standing static posture assessment as well as in a forward bending assessment, such as the sit and reach test. The natural (neutral) alignment of the spine is a skinny ‘S’ when observed from the side in a static posture assessment. The natural alignment of the spine in a forward bend is ‘global flexion’ of the spine, or an evenly proportioned arch. Excessive Kyphosis will stand out in each assessment.

In a static posture assessment, the skinny ‘S’ balloons in the top curve and becomes a fatter ‘S’. Meanwhile, the evenly arched spine in the forward bend also balloons through the rib cage, assimilating a ‘hunchback-like’ curvature.

Excessive Kyphosis does not exist in isolation; it is accompanied by other types of compensation patterns and Movement Dysfunctions. This, along with an excessively Kyphotic alignment of the spine, are other compensation patterns an individual may not realize he/she possesses.

RX: Practice a combination of soft tissue therapy and effective stretching techniques on muscles that connect to and around the Rib Cage and Thoracic Spine. These muscles include: the Upper Trapezius (Neck and Shoulder Muscle), Pectoral Complex (Chest Muscles), Latissimus Dorsi (Back Muscles), Psoas (Deep Hip Flexors), Tensor Fasciae Latae (TFL – Superficial Hip Flexor), Lower Erector Spinae (Low Back Muscles), Lower Multifidus (Low Back Muscles), Iliocostalis Lumborum (Low Back Muscles), and Quadratus Lumborum (Low Back Muscles).

Next, practice Activation exercises to strengthen and facilitate proper firing sequences of the following underactive muscles: Rhomboids (Upper Back Muscle), Mid and Lower Trapezius (Upper Back Muscles), Serratus Anterior (Shoulder Girdle Muscle), Rectus Abdominis (Anterior Core Muscles), Internal/External Obliques (Lateral Core Muscles), and Transverse Abdominis (Interior Core Muscles).

Finally, practice a variety of exercises integrating these underactive muscles with larger Movement Patterns, including Overhead and Horizontal Presses, Vertical and Horizontal Pulls, Diagonal 1 & 2 Movements (Chops and Lifts), and Swings. Also challenge stability, coordination, and balance with single-arm (unilateral) and/or locomotive (crawling/climbing) exercises.

Forward Head Posture

The Forward Head Posture or Forward Head Alignment is a compensation pattern prevalent in developed societies due to the combination of high levels of physical inactivity and high over usage rates of electronic devices.

In this compensation pattern, the cervical (neck) and suboccipital (head) muscles become overactive and tight due to the demand to position the head to optimally view an electronic device, screen, or point of interest. At the same time, the muscles of the torso, hips, and legs are biomechanically designed to support the positioning of the head. However, these latter muscles become inhibited and/or weakened in comparison to head and neck muscles due to the imbalance between physical activity (movement of the body) and mental/communication activity (stimulation of the mind and head sensory organs). The end result is head and neck muscles compensating for the lack of synergistic support from the rest of the body, leading to tightened muscles and transformed head/neck alignment.

Worse of all, Forward Head Posture is a drastically inefficient biomechanical alignment and position. The Head weighs (on average) 12lbs; for every inch the Head is moved ahead of natural alignment, the ‘mechanical’ weight of the head doubles. Thus, an individual whose head protrudes an inch out of alignment essentially is holding and moving a 24lb Head due to the mechanical disadvantage of this posture. Additionally, Forward Head Posture disrupts the natural flow of kinetic energy through the Spine as well as the rest of the body. This disruption in kinetic energy causes the individual to alter his Movement Patterns thereby creating patterns of compensation.

Many times, Forward Head Posture exists in combination with Excessive Kyphosis, Rounded Shoulders, Upper Cross Syndrome and Shoulder Impingement.

RX: Practice a combination of soft tissue therapy and effective stretching techniques on muscles that connect to the Head, Neck (Cervical Spine), and Rib Cage (Thoracic Spine). These muscles include: the Suboccipital Triangle (Posterior Head/Neck Muscles), the Upper Trapezius (Neck and Shoulder Muscle), Scalenes (Neck Muscles) and the Pectoral Complex (Chest Muscles).

Next, practice Activation exercises to strengthen and facilitate proper firing sequences of the following underactive muscles: Rhomboids (Upper Back Muscle), Mid and Lower Trapezius (Upper Back Muscles), Serratus Anterior (Shoulder Girdle Muscle), and the Cervical Flexors (Anterior Neck Muscles).

Finally, practice a variety of exercises integrating the corrected Neck Alignment with all other Movement Patterns.

Rounded Shoulders

Customarily, Internally Rotated and Protracted Shoulder alignment is the biomechanical description of ‘rounded shoulders.’

Rounded Shoulders is a compensation pattern that usually develops from the overuse of pushing or pressing exercises that cause the Pectoralis Complex (Chest Muscles) to be overactive and/or tight in relation to the Posterior Muscles, specifically the Rhomboids, Lower and Mid-Trapezius, and the external rotators of the Shoulders (Infraspinatus and Teres Minor).

The Strength Imbalance associated with Rounded Shoulders reduces the stability and mobility of the shoulder, which can lead to acute injury or prolonged inappropriate wear-and-tear of the shoulder. Muscles activated in the compensation include some physiological (soft tissue and joint) structures that when overused can lead to shoulder impingement or injury in the future.

Rounded Shoulders also influences the development of Forward Head Posture and Excessive Kyphosis, not to mention an integral part of Upper Cross Syndrome.

RX: Practice a combination of soft tissue therapy and effective stretching techniques on muscles that connect to and around the Rib Cage and Thoracic Spine. These muscles include: the Upper Trapezius (Neck and Shoulder Muscle), Pectoral Complex (Chest Muscles), and Latissimus Dorsi (Back Muscles).

Next, practice Activation exercises to strengthen and facilitate proper firing sequences of the following underactive muscles: Rhomboids (Upper Back Muscle), Mid and Lower Trapezius (Upper Back Muscles), Serratus Anterior (Shoulder Girdle Muscle), and Teres Minor and Supraspinatus (External Rotators in the Shoulder).

Finally, practice a variety of exercises integrating these underactive muscles with larger Movement Patterns, including Overhead and Horizontal Presses, Vertical and Horizontal Pulls, Diagonal 1 & 2 Movements (Chops and Lifts), and Swings. Also, challenge stability, coordination, and balance with single-arm (unilateral) and/or locomotive (crawling/climbing) exercises.

Upper Cross Syndrome

The Upper Cross Syndrome has a similar schematic framework as Lower Cross Syndrome, both of which are compensation patterns discovered and studied by Vladimir Janda, a renowned physical therapist.

The Upper Cross Syndrome is characterized by a combination of Strength (Muscle) Imbalances around the Shoulder Girdle and Thoracic Spine. In this compensation pattern, the shoulder girdle is held in a protracted position while the Thoracic Spine experiences excessive flexion in its alignment due to overactive and/or tight Pectoralis (Chest) Muscles and overactive and/or tight Upper Trapezius (Shoulder and Neck) muscles. These are in combination with underactive and/or weak Mid-to-Lower Trapezius and Rhomboid (Back) Muscles as well as underactive and/or weak Cervical Spine Flexors (Anterior Neck Muscles).

In short, the muscles of the chest and upper shoulders/neck area remain in contracted or shortened states. The reciprocal pairing of the anterior neck and upper back muscles are held in a lengthened state that altogether offers a great mechanical disadvantage to the mobility and stability of the shoulders. Additionally, Upper Cross Syndrome can be viewed as the combination of two compensation patterns: Excessive Kyphosis and Rounded Shoulders.

Upper Cross Syndrome presents barriers in efficiency and lowers the Movement Quality of all upper-body-centric movements as well as influences the alignment and movement of the Lumbar Spine, Pelvis, and Feet. Essentially, Upper Cross Syndrome can lead to injury (including Rotator Cuff tears) and Movement Dysfunctions (such as Low Back Pain) in any part of the body.

Many times, an individual develops the Upper Cross Syndrome through a combination of Lifestyle Factors including computer work, wearing a backpack, prolonged periods of sitting and even texting. It is also heavily influenced by the high volume of training or exercising ‘mirror muscles,’ or, the muscles predominantly visible in the mirror, i.e. the chest, abdominals, biceps, and anterior shoulders.

RX: The ultimate goal is to ‘re-educate’ the body’s habit of holding (continuously using) this pattern of compensation.

Start with a combination of soft tissue therapy and effective stretching techniques on muscles that connect to and around the Head, Neck (Cervical Spine), and Rib Cage (Thoracic Spine). These muscles include: the Suboccipital Triangle (Posterior Head and Neck Muscles), Scalenes (Neck Muscles), Upper Trapezius (Neck and Shoulder Muscle), Pectoral Complex (Chest Muscles), and Latissimus Dorsi (Back Muscles).

Next, practice Activation exercises to strengthen and facilitate proper firing sequences of the following underactive muscles: the Cervical Flexors (Anterior Neck Muscles), Rhomboids (Upper Back Muscle), Mid and Lower Trapezius (Upper Back Muscles), Serratus Anterior (Shoulder Girdle Muscle), Teres Minor and Supraspinatus (External Rotators in the Shoulder).

Finally, practice a variety of exercises integrating these underactive muscles with larger Movement Patterns, including Overhead and Horizontal Presses, Vertical and Horizontal Pulls, Diagonal 1 & 2 Movements (Chops and Lifts), Swings. Also, challenge stability, coordination, and balance with single-arm (unilateral) and/or locomotive (crawling/climbing) exercises.

Winged Scapula

Many times, an individual with Upper Cross Syndrome will also exhibit a ‘winged scapula’ at the same time. This compensation pattern occurs when there is a Strength or Muscle Imbalance around the Scapula, which forces the flat, triangular bone to re-position and hold in an internally rotated and/or anterior tilted alignment.

A winged scapula occurs when the Pectorals (Chest) and Upper Trapezius (Shoulder/Neck) Muscles are overactive and/or tight in comparison to the Lower/Mid Trapezius (Back) and the Serratus Anterior (Rib Cage) Muscles. This Strength/Muscle Imbalance shifts and holds the Scapula in a forward tilted position so the Medial (Inside) Ridge of the bone sticks out, away from the Rib Cage, like a ‘wing.’

A Winged Scapula compromises the Biomechanical Integrity of the Shoulder and causes other muscles, such as the Pectorals and Upper Trapezius muscles, to overcompensate their contractile pull on the Scapula to create enough stability for any movement utilizing the Arms and/or Upper Body.

RX: Practice a combination of soft tissue therapy and effective stretching techniques on muscles that connect to and around the Rib Cage (Thoracic Spine), Scapula, and Shoulder. These muscles include: the Upper Trapezius (Neck and Shoulder Muscle), Pectoral Complex (Chest Muscles), and Latissimus Dorsi (Back Muscles).

Next, practice Activation exercises to strengthen and facilitate proper firing sequences of the following underactive muscles: Rhomboids (Upper Back Muscle), Mid and Lower Trapezius (Upper Back Muscles), Serratus Anterior (Shoulder Girdle Muscle), and Teres Minor and Supraspinatus (External Rotators in the Shoulder).

Finally, practice a variety of exercises integrating these underactive muscles with larger Movement Patterns, including Overhead and Horizontal Presses, Vertical and Horizontal Pulls, Diagonal 1 & 2 Movements (Chops and Lifts), Swings. Also, challenge stability, coordination, and balance with single-arm (unilateral) and/or locomotive (crawling/climbing) exercises.

Shoulder Impingement

The National Academy of Sports Medicine reports that 40% of shoulder pain is a result of shoulder impingement. Approximately half of those individuals experience a recurrence of pain within the next two years, even after being assessed and treated. These numbers suggest that any trainer or coach has a high probability of training an athlete/client who has or had a shoulder impingement. Therefore, understanding how to detect and address a shoulder impingement is very beneficial.

Many times, Shoulder Impingement occurs simultaneously with other compensation patterns including Upper Cross Syndrome, Rounded Shoulders, Excessive Kyphosis, and Forward Head Posture.

Mechanics of a Shoulder Impingement

A Shoulder Impingement usually occurs from repetitive movements in an anterior (forward) and superior (upward) direction, such as a high volume of pushing or pressing exercises (like the bench press) and/or an overuse of certain Daily Life Activities including computer work and driving.

Repetitive movements and overuse in an anterior (forward) and superior (upwards) direction creates overactive muscles and a level of tightness in the Pectorals (Chest), Anterior Deltoid (Shoulder), and Upper Trapezius (Neck/Shoulder) Muscles. The resulting tightness of these muscles compresses or sequences the Shoulder Complex until the Acromian Process (front portion of the Scapula that connects with the Collar Bone) presses down onto the soft tissue below it causing an abnormal amount of friction when the Shoulder is in motion. Essentially, the friction caused by the compression from the Shoulder Complex accelerates the ‘wear-and-tear’ of the soft tissue below the Acromian Process, causing pain in addition to possibly leading to a rupture or tear of these tissues.

RX: One of the main objectives of the treatment of a Shoulder Impingement is to create more ‘space’ under the Acromian Process by using a combination of stiff tissue therapy and stretching to lengthen the short, tight, and overactive muscles, specifically the Pectorals (Chest), Deltoid (Shoulder), and Upper Trapezius (Neck/Shoulder) muscles that connect to the Shoulder Complex. Once the tightness in these tissues is addressed, the next step is to increase the Range of Motion and stability of the entire Shoulder Complex as a way to prevent a Shoulder Impingement from reoccurring.

Start with a combination of soft tissue therapy and effective stretching techniques on muscles that connect to and around the Rib Cage (Thoracic Spine), Scapula and Shoulder. These muscles include: the Upper Trapezius (Neck and Shoulder Muscle), Pectoral Complex (Chest Muscles), Anterior Deltoids (Shoulders), and Latissimus Dorsi (Back Muscles).

Next, practice Activation exercises to strengthen and facilitate proper firing sequences of the following underactive muscles: Rhomboids (Upper Back Muscle), Mid and Lower Trapezius (Upper Back Muscles), Serratus Anterior (Shoulder Girdle Muscle), and Teres Minor and Supraspinatus (External Rotators in the Shoulder).

Finally, practice a variety of exercises integrating these underactive muscles with larger Movement Patterns, including Overhead and Horizontal Presses, Vertical and Horizontal Pulls, Diagonal 1 & 2 Movements (Chops and Lifts), Swings. Also, challenge stability, coordination, and balance with single-arm (unilateral) and/or locomotive (crawling/climbing) exercises.

Elevated Shoulders

Many people experience the Compensation Pattern of Elevated Shoulders due to the Daily Life Activities of driving, working on a computer, working at a desk, and carrying bags on their shoulders. For many individuals, this pattern of compensation occurs simultaneously with the Upper Cross Syndrome and Forward Head Posture.

Elevated Shoulders is essentially a compensation pattern based on a Strength or Muscle Imbalance around the Shoulder. In this pattern, the shoulders are raised or ‘elevated’ by the Upper Trapezius and Scalenes (Neck/Shoulder) Muscles in an attempt to stabilize and control the Scapula and Arm because the inferior (below) synergistic muscles of the Serratus Anterior (Rib Cage), Rhomboids (Back), and Lower/Mid Trapezius (Back) muscles are not adequately firing and providing stability to the Shoulder Complex.

Since the Scapula acts as a platform for the Shoulder and Arm to move upon, the lack of synergistic support from the Serratus Anterior, Rhomboids, and Mid/Lower Trapezius muscles only compromises the positioning of the Scapula, thus compromising the movement of the Arm and Shoulder. This compensation pattern inadvertently places an inappropriate amount of strain onto the Cervical Spine (Neck), weakening the force output of the Arms and Shoulders.

RX: The first step is to use soft tissue therapy and stretching to lengthen and release tension in the tight and overactive muscles that elevate the shoulders. The next step is to focus on activating/strengthening muscles that can depress or anchor the Shoulder Girdle onto the Rib Cage with support of the Trunk (Core) Muscles.

Start with a combination of soft tissue therapy and effective stretching techniques on muscles that connect to and around the Rib Cage and Thoracic Spine. These muscles include: the Upper Trapezius (Neck and Shoulder Muscle), Scalenes (Neck Muscles), Pectoral Complex (Chest Muscles), and Latissimus Dorsi (Back Muscles).

Next, practice Activation exercises to strengthen and facilitate proper firing sequences of the following underactive muscles: Rhomboids (Upper Back Muscle), Mid and Lower Trapezius (Upper Back Muscles), Serratus Anterior (Shoulder Girdle Muscle), Rectus Abdominis (Anterior Core Muscles), Internal/External Obliques (Lateral Core Muscles), and Transverse Abdominis (Interior Core Muscles).

Finally, practice a variety of exercises integrating these underactive muscles with larger Movement Patterns, including Overhead and Horizontal Presses, Vertical and Horizontal Pulls, Diagonal 1 & 2 Movements (Chops and Lifts), Swings. Also, challenge stability, coordination, and balance with single-arm (unilateral) and/or locomotive (crawling/climbing) exercises.

Uneven Shoulders

One of the most difficult patterns of compensation to assess, ‘Uneven Shoulders’ is a complicated Strength or Muscle Imbalance occurring in many people without their knowledge. This pattern of compensation usually develops in an individual due to a previous injury and/or lifestyle factors, including simple habits such as carrying a bag on only one shoulder.

Uneven shoulders are easily observed in a static posture assessment. However, the causes or the nature of the Strength/Muscle Imbalance involved in this compensation pattern is not as easily noticeable due to the complex nature of the movement of the Hips, Torso/Core, and Shoulders. In some individuals, the Upper Trapezius (Neck/Shoulder) Muscle may be tight and overactive, while in others it may be the Latissimus Dorsi (Back) or Pectoralis (Chest) or even the Quadratus Lumborum (Low Back) Muscles that are tight and overactive.

RX: Use soft tissue therapy and stretching techniques to systematically address all muscles in the body. Practice movement in training with the largest Range of Motion possible for the individual. Additionally, attempt to change simple Daily Life Activities, such as wearing a bag on the opposite shoulder and opening doors with the opposite (non-dominant) hand. The combination of mobility training with the change of Daily Life Activities will help eliminate the repetitive movements that create ‘Uneven Shoulders’ and have a negative effect on posture.

Hyperinflation

Most people take the act of breathing for granted. Not too many people pay much attention to breathing, let alone the mechanics involved. However, the mechanics of breathing have a huge influence over an individual’s posture and movement.

Hyperinflation refers to the habitual process of inhaling and/or holding onto the inhalation of a breath cycle to the point that the Rib Cage and muscles surrounding the Thoracic Cavity (Upper Torso) are held in an expanded or semi-expanded position. In other words, Hyperinflation is the continual act of not breathing out deeply enough to fully clear the lungs of air and contract the Rib Cage.

Does Hyperinflation really matter? Yes. Hyperinflation can disrupt an individual’s movement both mechanically and physiologically.

In mechanical terms, Hyperinflation keeps the Rib Cage expanded, diverting the flow of kinetic energy through the body, forcing certain muscles to compensate for the abnormal flow of energy. Additionally, Hyperinflation creates tightness in the muscles associated with the inhalation cycle of the breath, namely the Upper Trapezius (Neck/Shoulder) Muscles.

In physiological terms, Hyperinflation reduces stimulation of the Parasympathetic Nervous System, which normally lets the muscles release held contractions, restores their natural lengths, and regenerates soft tissue cells that aid in an individual’s full recovery from bouts of training as well as from Daily Life Activities.

It is nearly impossible to correct any pattern of compensation if it is undetected. Therefore, it’s important to have some keys or guidelines to use when assessing for hyperinflation. So, what does Hyperinflation look like?

First, observe the movement of the Rib Cage and Thorax (Torso) while breathing. Notice if the Chest and Shoulders rise and fall or if the belly and Thorax (Torso) as a whole rise and fall. The latter is the more appropriate mechanic for breathing. Also, observe the individual for the pattern of ‘Flared Ribs’ where the lower ribs ‘stick out,’ a dysfunction that commonly occurs simultaneously with Hyperinflation.

Next, time the duration of an inhale (breath in) compared to the length of an exhalation (breath out). Are they even? Can the individual maintain an even cycle of inhale/exhale for ten full cycles? These are easy observations to integrate while observing the mechanics of the Thorax (Torso) and Rib Cage to get insight in an individual’s habit of breathing. Some people may be able to establish an even breath cycle for a few breaths, but habitually become hyper-inflated when left unchallenged.

Lastly, watch the individual breathe while moving, especially when performing stretches and/or exercises. Observing an individual’s breathing mechanics while moving reveals breathing habits. Do they hold their breath when they move? Do they breathe easy and evenly? What happens when they are cued to exhale? How long can the individuals breathe easily and evenly after cuing? These are all questions to ask to get insight in individuals’ breathing habits.

RX: One very effective exercise to teach an individual proper breathing technique is simply lying on the floor while blowing up balloons.

Jason Masek, MA, PT, ATC, CSCS, PR uses balloons as an exercise at the University of Nebraska to teach proper breathing mechanics that focus on strong exhalation, also inducing the Parasympathetic Nervous System to calm the student-athletes before training or competition.

‘Blowing up balloons’ is a very effective exercise that can be practiced anywhere, even without balloons. Simply imagining the act of blowing up a balloon trains proper breathing mechanics and restores mobility and function to the entire Thorax (Torso) and Rib Cage.

Recap: Common Patterns of Compensation

The Human Body is continuously being shaped and remodeled by Human Movement in ‘machotransduction,’ a process in which the forces experienced by the cells of the body in any and all movement physiologically change the cell in direct correlation to the direction and magnitude of those forces. Sometimes, as in patterns of compensation, this process of re-modeling the body increases inefficiencies and can even lead to injury. However, an individual can marginalize, if not eliminate, the risk of inefficiency and injury by observing patterns of compensation and then actively working to correct the associated Movement Dysfunctions.

‘Common’

Due to similarities in Lifestyle and Daily Life Activities in the modern developed world, a collection of ‘common’ or readily recurring compensation patterns and Movement Dysfunctions has been developed. This list can be used by trainers, coaches, and individuals to guide their own observations and assessment of movement to proactively reduce and/or eliminate risk of injury and inefficiency.

Resources

Assessment and Treatment of Muscle Imbalance: The Janda Approach.

P Page, C Frank, R Lardner, editors. Human Kinetics: Windsor, Ontario, Canada

Clark MA, Lucett SL. NASM Essentials of Corrective Exercise Training, Baltimore, MD:Lippincott Williams & Wilkins;2011.

Clark MA, Lucett SL. NASM Essentials of Personal Fitness Training 4th ed. Baltimore, MD:Lippincott Williams & Wilkins;2012.

Baechle, Earle. Essentials of Strength Training and Conditioning – Third Edition – National Strength & Conditioning Association – Hong Kong, Human Kinetics; 2008

Bron C, Dommerholt J. Etiology of Myofascial Trigger Points, Current Pain Headache Report, 2012 Oct; 16(5): 439-444

Joint Structure and Function – Fifth Edition – A Comprehensive Analysis by Pamela Levangie and Cynthia Norkin, F.A. Davis Company – Philadelphia 2011

The Whartons’ Stretch Book – Featuring the Breakthrough Method of Active-Isolated Stretching by Jim and Phil Wharton, Three Rivers Press, New York 1996

Biomechanics – A Qualitative Approach for Studying Human Movement by Ellen Kreighbaum and Katharine Barthels – Allyn and Bacon – Boston 1996

Biomechanics in the Musculoskeletal System by Manohar Panjabi and Augustus White – Churchill Livingstone – New York – 2001

Applied Kinesiology – Revised Edition – A Training Manual and Reference Book of Basic Principles and Practices – Robert Frost –North Atlantic Books – Berkley 2013

Bowman K, Move Your DNA, USA, First Printing, 2014

Starrett K, Cordoza G, Becoming a Supple Leopard, USA, Victory Belt Publishing, 2013

Myers T, Anatomy Trains, USA, Churchill Livingstone Elsevier, 2014

Restricted Hip Mobility: Clinical Suggestions for Self-Mobilization and Muscle Re-Education – Michael Reiman and JW Matheson – Int J Sports Phys Ther. 2013 Oct; 8(5): 729–740. PMCID: PMC3811738

Bruce Kelly, MS, CSCS, NSCA-CPT, NASM-PES, The Importance of Mobility

http://www.fitness-nutrition-weightloss.com/the-importance-of-mobility.html

James Hoffman, MS, BS, A Different Approach to Mobility

http://www. jtsstrength.com/articles/2014/10/13/different-approach-mobility/

diZerega, Gere; Campeau, Joseph (2001). “Peritoneal repair and post-surgical adhesion formation” (PDF). Human Reproduction Update 7 (6): 547–555. doi:10.1093/humupd/7.6.547. Retrieved 22 May 2014.

Liakakos, T., Thomakos, N., Fine, P., Dervenis, C., & Young, R. (2001). Peritoneal adhesions: etiology, pathophysiology, and clinical significance. Recent advances in prevention and management. Dig Surg, 18(4), 206–273.

Junker, Daniel H.; Stöggl, Thomas L., The Foam Roll as a Tool to Improve Hamstring Flexibility, Journal of Strength and Conditioning Research, December 2015, Vol. 29 – Issue 12: p 3480–3485

Scand J Med Sci Sports. 2010 Aug;20(4):580-7. Iliotibial band syndrome: an examination of the evidence behind a number of treatment options

Scott Lawrance, DHS, LAT, ATC, MSPT, CSCS, Unlock the Hip: Using Joint Mobilization to Improve Mobility – Great Lakes Athletic Trainers’ Association45th Annual Winter Meeting – Wheeling, IL, March 16, 2013

One thought on “List of Common Compensation Patterns and Movement Dysfunctions”

Comments are closed.